Unlike OpenGL where (at least using GLUT) we had a working application rendering graphics with only a few lines of code, it has taken us three periods to get to the point to even begin to render geometry with DirectX 10. Fortunately most of the framework we have developed can serve as the basis for a majority of our programs as it will load shaders and render geometry.

Our application is now ready to render geometry using a shader, so the next step is to create some geometry. Usually a 3D modeling program (such as 3ds Max or Blender) is used to create complex object geometries (and apply textures, etc.) which are then loaded into the DirectX application using a model loader. Later in this course we will see how to use Blender to create models and use an importer to bring them into our application framework by defining a Mesh class. For now we will just create geometry directly in the application (similar to OpenGL) to understand how it is handled.

0. Getting Started

Navigate into the CS370_Lab03 directory and double-click on CS370_Lab03.sln (the file with the little Visual Studio icon with the 12 on it) which should immediately open another instance of Visual Studio with the project.

If the Header Files, Resource Files and Source Files folders in the Solution Explorer pane are not expanded, expand each by double clicking on them and double-click on Cube.h and Cube.cpp.

1. Cube Declaration

Double-click Cube.h which should have a skeleton structure already in the file with the method prototypes already in place.

At this point we are ready to add the class attributes (variables) in the private section. Note that by convention, class attributes begin with m. The following set of attributes will store information about the cube object such as the number of vertices, number of faces, and number of edges which will be used when we create the vertex and index buffers (remember them from CS370?). We also store pointers to some COM objects DirectX will use to render the object.

// Geometry values

DWORD mNumVertices;

DWORD mNumFaces;

DWORD mNumEdges;

// DirectX objects

ID3D11Buffer* mVertexBuffer;

ID3D11Buffer* mIndexBuffer;

2. Cube Definition

Double-click Cube.cpp which should have a skeleton structure already in the file with stubs for all the methods.

First we need define a structure to describe what information will be stored for each vertex (refer back to the vertex layout section of the application class) which in this case will be a 3D vector for the position and a 4D vector for the color. Later we will extend this structure to contain fields for vertex normals (lighting) and texture coordinates.

#include "Cube.h"

// Vertex structure

struct Vertex {

XMFLOAT3 pos;

XMFLOAT4 color;

};

Constructor

The constructor just initializes all the attributes to 0.

// Constructor

Cube::Cube() : mNumVertices(0),mNumFaces(0),mVertexBuffer(0),mIndexBuffer(0)

{

}

Destructor

The destructor will need to release the two buffer COM objects we will be initializing.

// Destructor

Cube::~Cube()

{

ReleaseCOM(mVertexBuffer);

ReleaseCOM(mIndexBuffer);

}

Initialization

The Init() method will do most of the heavy lifting in terms of defining a vertex array with the coordinates of the vertices and assigning a color to them, creating an index array to specify which vertices belong to which polygon (remember we are using triangle list primative topology), and then create the corresponding vertex and index buffers using these arrays.

We will want to add edges to our cube faces, since they are a different color we need 16 vertices - the first 8 for the faces (colored) and the last 8 for the edges (black). There will be two triangles needed to draw each (square) face, so we need 12 faces (which will be defined in the index array). Finally since each of the 6 faces has 4 edges there will be a total of 24 edges.

// Set instance attributes (2 triangles per face)

mNumVertices = 16;

mNumFaces = 12;

mNumEdges = 24;

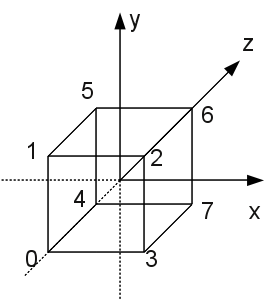

Remembering that DirectX utilizes a left-handed coordinate system, we can list the vertices of the cube according to the following picture:

// Create vertex array

Vertex vertices[] =

{

// face vertices

{ XMFLOAT3(-1.0f, -1.0f, -1.0f), (const float*)&Colors::White },

{ XMFLOAT3(-1.0f, +1.0f, -1.0f), (const float*)&Colors::Black },

{ XMFLOAT3(+1.0f, +1.0f, -1.0f), (const float*)&Colors::Red },

{ XMFLOAT3(+1.0f, -1.0f, -1.0f), (const float*)&Colors::Green },

{ XMFLOAT3(-1.0f, -1.0f, +1.0f), (const float*)&Colors::Blue },

{ XMFLOAT3(-1.0f, +1.0f, +1.0f), (const float*)&Colors::Yellow },

{ XMFLOAT3(+1.0f, +1.0f, +1.0f), (const float*)&Colors::Cyan },

{ XMFLOAT3(+1.0f, -1.0f, +1.0f), (const float*)&Colors::Magenta },

// edge vertices

{ XMFLOAT3(-1.0f, -1.0f, -1.0f), (const float*)&Colors::Black },

{ XMFLOAT3(-1.0f, +1.0f, -1.0f), (const float*)&Colors::Black },

{ XMFLOAT3(+1.0f, +1.0f, -1.0f), (const float*)&Colors::Black },

{ XMFLOAT3(+1.0f, -1.0f, -1.0f), (const float*)&Colors::Black },

{ XMFLOAT3(-1.0f, -1.0f, +1.0f), (const float*)&Colors::Black },

{ XMFLOAT3(-1.0f, +1.0f, +1.0f), (const float*)&Colors::Black },

{ XMFLOAT3(+1.0f, +1.0f, +1.0f), (const float*)&Colors::Black },

{ XMFLOAT3(+1.0f, -1.0f, +1.0f), (const float*)&Colors::Black }

};

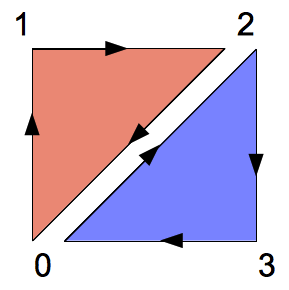

Since we are using a triangle list to draw the faces, we need to observe the left-hand rule to order our vertices to ensure the correct outward facing normal (i.e. the front face). For example the front face (the one at z = -1) could be divided up into two triangles with vertices (0,1,2) [red] and (0,2,3) [blue] as shown below

When we draw, we are able to specify which vertex to start with. This allows us to begin indexing at 0 for each separate object in the vertex array (although we can always simply continue the index numbering). This is often very convenient when we have several objects (and index arrays) created separately that we wish to combine into single vertex/index arrays since we do not need to renumber the indices for subsequent objects. Hence the index array can be constructed as follows

// Create index array

DWORD indices[] =

{

// Front face

0,1,2,

0,2,3,

// Back face

4,6,5,

4,7,6,

// Left face

4,5,1,

4,1,0,

// Right face

3,2,6,

3,6,7,

// Top face

1,5,6,

1,6,2,

// Bottom face

4,0,3,

4,3,7,

// Front edges

0,1,2,3,0,

// Back edges

4,5,6,7,4,

// Left edges

4,5,1,0,4,

// Right edges

3,2,6,7,3,

// Top edges

1,5,6,2,1,

// Bottom edges

4,0,3,7,4

};

We now create the vertex buffer (similar to our other COM objects) by initializing the fields of a descriptor variable including the total size of the vertex array and the type of buffer the data should be used for. We then create a resource variable and set its data field to our vertex array.

// Create vertex buffer

D3D11_BUFFER_DESC vbd;

vbd.Usage = D3D11_USAGE_IMMUTABLE;

vbd.ByteWidth = sizeof(Vertex)*mNumVertices;

vbd.BindFlags = D3D11_BIND_VERTEX_BUFFER;

vbd.CPUAccessFlags = 0;

vbd.MiscFlags = 0;

vbd.StructureByteStride = 0;

D3D11_SUBRESOURCE_DATA vinitData;

vinitData.pSysMem = vertices;

HR(device->CreateBuffer(&vbd, &vinitData, &mVertexBuffer));

Similarly we create the index buffer using our index array (note the calculation used for the total number of indices, particularly the number of edges where each edge loop has one extra vertex to complete the loop)

// Create index buffer

D3D11_BUFFER_DESC ibd;

ibd.Usage = D3D11_USAGE_IMMUTABLE;

ibd.ByteWidth = sizeof(DWORD)*(mNumFaces * 3 + (mNumEdges + 6));

ibd.BindFlags = D3D11_BIND_INDEX_BUFFER;

ibd.CPUAccessFlags = 0;

ibd.MiscFlags = 0;

ibd.StructureByteStride = 0;

D3D11_SUBRESOURCE_DATA iinitData;

iinitData.pSysMem = indices;

HR(device->CreateBuffer(&ibd, &iinitData, &mIndexBuffer));

Draw

At last the Draw() method can render the geometry stored in the vertex and index buffers through the immediate context of the device. To do this we need to tell DirectX where to start in the vertex buffer (i.e. we can store several different objects in a single vertex buffer as we are doing with the faces and edges) and how far to step (i.e. stride) based on the size of the vertex structure. We then simply set the topology (to be sure it is correct for this object) and tell DirectX to draw using indexed mode by passing how many indices to render, which index to start at, and where in the vertex buffer to start (remember that we indexed the edges starting at the middle vertex in the array).

// Step by Vertex size

UINT stride = sizeof(Vertex);

// Start at beginning of buffer

UINT offset = 0;

// Set buffers for device

immediateContext->IASetVertexBuffers(0, 1, &mVertexBuffer, &stride, &offset);

immediateContext->IASetIndexBuffer(mIndexBuffer, DXGI_FORMAT_R32_UINT, 0);

// Draw faces

immediateContext->IASetPrimitiveTopology(D3D10_PRIMITIVE_TOPOLOGY_TRIANGLELIST);

immediateContext->DrawIndexed(mNumFaces * 3, 0, 0);

// Draw edges

immediateContext->IASetPrimitiveTopology(D3D10_PRIMITIVE_TOPOLOGY_LINESTRIP);

immediateContext->DrawIndexed((mNumEdges + 6), mNumFaces * 3, mNumVertices / 2);

3. Shader (Effects) File

DirectX 11 (and the recent version of OpenGL) forego the default graphics pipeline architecture relying instead completely on programmable shaders - known as effects - to render geometry. DirectX shaders are comprised of at least one vertex and one pixel shader that are combined into a technique. An effects file may contain multiple different shaders (including an additional geometry shader) that can be assembled in different combinations to create multiple techniques (that are selected in the application as desired).

Just like GLSL, HLSL (the DirectX shader language) associates pointers in the application with variables in the shader and then sets values for these variables through the application pointer (refer back to the last part of the buildFX() method definition in the previous lab).

We will add the effects file into Resource Files. Create a new text file (right click the Resource Files folder and select Add->New Item... making sure to choose Utility and Text File (.txt)) named basiccube.fx.

We now need to adjust the properties of basiccube.fx by right clicking on it and selecting Properties. Under HLSL Compiler->General change Shader Type to Effect (/fx) and Shader Model to Shader Model 5 (/5_0) (see the D3DX11CompileFromFile() call in buildFX() method).

Shader Variables

First we will define one global matrix passed from the application which will store the complete world-view-projection matrix (i.e. similar to the gl_ModelViewProjectionMatrix variable from GLSL). This variable will be a constant buffer that will only change on a per object basis.

// World-View-Projection matrix buffer

cbuffer cbPerObject

{

float4x4 gWVP;

};

Vertex Shader

Since the vertex shader will need to input and output multiple pieces of information (i.e. vertex position and color which must match the vertex layout defined in our buildVertexLayouts() method), we will define structs for the input and output vertex component types (note they are not the same).

We will name our vertex shader VS() (although any valid C syntax function name may be used) which takes an input vertex struct and will output the transformed vertex struct. The vertex transformation calculation will simply multiply the (homogeneous) vertex coordinates by the (shader) world-view-projection matrix. Finally the vertex shader will just pass the color down the pipeline unchanged.

// Input vertex datatype

struct VIn

{

float3 inPos : POSITION;

float4 inCol : COLOR;

};

// Output vertex datatype

struct VOut

{

float4 pos : SV_POSITION;

float4 col : COLOR;

};

// Vertex shader

VOut VS(VIn vin)

{

VOut vout;

// Apply world-view-projection transformation

vout.pos = mul(float4(vin.inPos, 1.0f), gWVP);

// Pass color through

vout.col = vin.inCol;

// Return transformed vertex

return vout;

}

Pixel Shader

Pixel shaders only return one value of type float4 named SV_TARGET which is the color to set the fragment in the render target. Since we do not have a geometry shader, the input datatype of the pixel shader will match the output datatype of the vertex shader.

We will name our pixel shader PS(), but again any valid C function name is allowed. This pixel shader will simply set the final fragment color to the one passed by the vertex shader (in the future we will apply lighting and textures here).

// Pixel shader

float4 PS(VOut pin) : SV_Target

{

// Simply set color

return pin.col;

}

Technique Description

Lastly, we need to tell DirectX which vertex and pixel (and possibly geometry) shaders to combine to create all the techniques we wish to use. Each technique is given a unique name (which is referenced by the application, recall buildFX() from the last lab). Techniques may also have multiple passes which can be used for multipass rendering techniques.

We will name the technique BasicTech and use our previously defined vertex (VS()) and pixel (PS()) shaders.

// Technique

technique10 BasicTech

{

pass P0

{

SetVertexShader(CompileShader(vs_5_0,VS()));

SetGeometryShader(NULL);

SetPixelShader(CompileShader(ps_5_0,PS()));

}

}

4. Compiling and running the program

Once you have completed typing in the code, you can build and run the program in one of two ways:

- Click the small green arrow in the middle of the top toolbar

- Hit F5 (or Ctrl-F5)

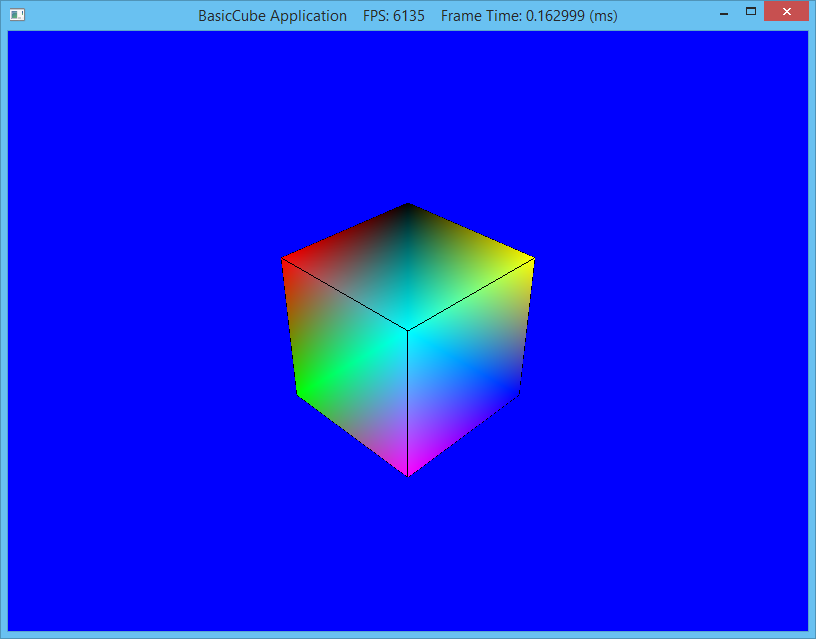

The output should look similar to below

To quit the program simply close the window.

Now that we have a functional program to render geometry, we need to add all the effects that we had from CS370 including lighting and texture mapping. These effects will require us to expand our vertex structure to include information about the normals and texture coordinates, pass additional information into the shaders, and finally add functionality into the shaders to apply these effects to our primatives. Eventually we will also start importing more complex geometry from external modeling programs.