Last class we performed a detailed analysis of insertion sort only to end up discarding most of the work by only keeping the highest order term. We intuitively described the asymptotic growth of a function based on the input size, i.e. for “sufficiently large” values of n. Formal mathematical notation can be used to both rigorously define the asymptotic behavior for a particular algorithm as well as serve as a mechanism to compare algorithms. Thus typically the asymptotic behavior is used to describe the efficiency of an algorithm without requiring computation of the exact run time.

We will want to find either or both an asymptotic lower bound and upper bound for the growth of our function. The lower bound represents the best case growth of the algorithm while the upper bound represents the worst case growth of the algorithm.

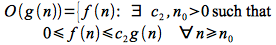

O() - (“Big O”)

As discussed in the previous lecture, often we are most concerned about the worst case behavior of an algorithm. Thus we define an asymptotic upper bound (although not necessarily tight) for a function f(n) denoted O() as follows: Given two functions f(n) and g(n)

Thus O() describes how bad our algorithm can grow, i.e. is no worse than. Note: Often it is enough to find a loose upper bound to show that a given algorithm is better than (or at least no worse than) another.

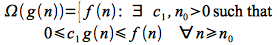

𝛀() - (“Big Omega”)

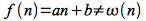

We can similarly define an asymptotic lower bound (again not necessarily tight and often not particularly useful) for a function f(n) denoted ω() as follows: Given two functions f(n) and g(n)

Thus ω() describes how good our algorithm can be, i.e. is no better than. For this bound to be meaningful, it is often best to find a tight lower bound.

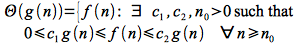

Θ() - (“Big Theta”)

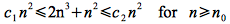

Finally we can define an asymptotically tight bound for a function f(n) denoted Θ() as follows: Given two functions f(n) and g(n) both asymptotically non-negative

This notation indicates that g(n) is both a lower bound (best case) and upper bound (worst case) for f(n), thus the algorithm has a consistent growth independent of the particular input set.

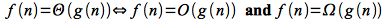

Theorem

For any two functions f(n) and g(n)

Intuitively, the theorem simply states that a function is an asymptotically tight bound if and only if it is both an upper and lower bound.

Examples

Example 1

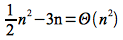

Show

Solution

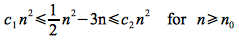

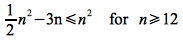

We need to find constants c1, c2, n0> 0 such that

Dividing through by n2 (which is valid since n>0) gives

Lower Bound

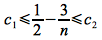

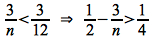

Consider the lower bound, i.e.

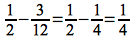

If we let n0 = 12, then the right hand side becomes

and for any n > 12

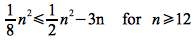

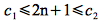

Hence we can choose c1 ≤ 1/4 (e.g. c1 = 1/8) and n0 = 12 to satisfy the lower bound since

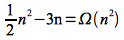

Therefore

Note: ANY combination of c1 and n0 that satisfy the lower bound may be used, but whichever ones are chosen must be constant values.

Upper Bound

Consider the upper bound, i.e.

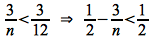

Again we use a similar procedure to the lower bound but with the same n0 = 12 (or any n0 > 12 since the lower bound holds for any n > 12), then the left hand side becomes

for any n > 12.

Hence we can choose c2 ≥ 1/2 (e.g. c2 = 1) and n0 = 12 to satisfy the upper bound since

Note: Again we may choose ANY c2 that satisfies the upper bound with the same n0 as the lower bound, but whichever one is chosen must be a constant value.

Example 2

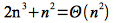

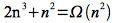

Determine if

Solution

As before, we need to find constants c1, c2, n0> 0 such that

Dividing through by n2 (which is valid since n>0) gives

Lower Bound

Consider the lower bound, i.e.

Clearly this lower bound can be satisfied for c1 = 1 and n0 = 1

Therefore

Upper Bound

Unfortunately we cannot find any constant c2 that satisfies

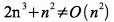

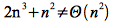

for all n (much less n ≥ n0). Therefore

Hence by the theorem

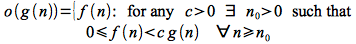

o() - (“Little O”)

A weaker (non-asymptotically tight) upper bound that is often useful and easier to determine is defined for two functions f(n) and g(n) as

This upper bound can be shown by the following limit

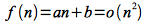

For example, it can easily be shown that

since

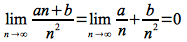

However

since

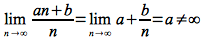

ω() - “Little Omega”

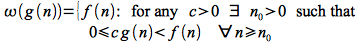

A corresponding weaker (non-asymptotically tight) lower bound is defined for two functions f(n) and g(n) as

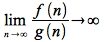

This lower bound can also be shown by the following limit

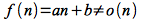

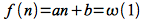

For example, it can easily be shown that

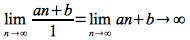

since

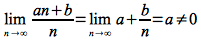

However

since

Summary

Intuitively, asymptotic notation can be thought of as “relational operators” for functions similar to the corresponding relational operators for values

= ⇒ Θ()

≤ ⇒ O()

≥ ⇒ Ω()

< ⇒ o()

> ⇒ ω()

Review properties of exponentials (pg. 55 of CLRS), logarithms (pg. 56 of CLRS), and summations (Appendix A of CLRS).