Big fleas have little fleas,

Upon their backs to bite ‘em,

And little fleas have lesser fleas,

and so, ad infinitum.

Learning goals

- Use turtle graphics and Processing drawing functions to generate images from simple rules

- Appreciate how self-similarity at varying scales leads to “natural”-looking images

- Understand how to use a recursive method to generate a fractal image

Getting started

To get started, do the following:

- Download ProcessingLibs.zip

- Open

ProcessingLibs.zipin a file browser - Copy the

Terrapinfolder (right click, then choose “Copy”) - In a file browser, navigate to your

Processingfolder - Navigate into the

librariesfolder inside yourProcessingfolder - Paste the

Terrapinfolder (right-click, then choose “Paste”)

Now, start Processing. The steps above install the Terrapin library that we will use for turtle graphics.

What to do

Your task is to use turtle graphics and Processing drawing functions to draw cool-looking images, and in particular, fractal images. The general idea is that the sketch should use a procedure based on simple rules to create the image.

That’s really the only task! Just mess around and see if you can create some interesting images by modifying and extending some of the examples shown below. Don’t forget to save your favorite sketches in your Processing sketchbook folder.

Each example below is a complete sketch. You can simply create a new sketch in Processing and then copy and paste the code. Use File → Save As… if you would like to save your own version of one of the example sketches.

Turtle graphics

Here’s a quick explanation of the turtle graphics commands used in some of the example sketches below. (Turtle graphics were invented as part of the Logo programming language, and have a long and rich history in programming and computer art.)

The code import terrapin.*; at the top of a sketch means we’re using the Terrapin Processing library. A Processing library adds new commands that you can use in your sketches to do cool things.

The code Terrapin t = new Terrapin(this); makes the variable t refer to a new Terrapin. You can think of a Terrapin as a turtle facing a particular direction and dragging a pen. By telling the turtle when to turn and when to move forward, you can use the turtle to draw shapes.

The code t.setLocation(x, y); sets the Terrapin’s location to the specified x/y coordinates. These might be literal values (e.g., 400, 300) or they could be variables.

The code t.setPenColor(r, g, b); sets the Terrapin’s pen color to the specified R/G/B values.

The code t.forward(dist); moves the Terrapin forward by the specified distance.

The code t.left(angle); and t.right(angle); rotates the turtle left or right by the specified angle. The angle is specified in degrees, e.g., 90 would indicate a 90 degree turn.

Example sketch 1: spiral

Here is a simple example:

import terrapin.*;

void setup() {

size(800,600);

background(235);

noLoop();

}

void draw() {

Terrapin t = new Terrapin(this);

t.setLocation(400,300);

t.setPenColor(15,40,199);

for (int i = 0; i < 500; i++) { // repeat 500 times

t.forward(i);

t.left(44);

}

}This example produces the following output (click for full size):

So, what is going on here?

- The

setupmethod sets the window size and background color, and usesnoLoopso that thedrawmethod is only executed once (i.e., it’s not an animation) - The

drawmethod creates a Terrapin (turtle), sets its location to 400,300 (at the center of the window), and sets its pen color to a shade of blue - The for loop repeats, for values of the variable

ifrom 0 to 499: move forwardipixels of distance, and then turn left 44 degrees

Try modifying this sketch. What happens if you change the amount by which the turtle moves forward at each step? (Try i*2 instead of i.) What happens if you change the turn angle to make it larger or smaller? What happens if you use the right command instead of left?

Example sketch 2: a fractal tree

Here is an example of a fractal:

import terrapin.*;

float startLen = 150;

float decay = .75;

int angle = 35;

void setup() {

size(800, 600);

background(235);

noLoop();

}

void draw() {

Terrapin t = new Terrapin(this);

t.setLocation(400,600);

t.setRotation(270);

t.setPenColor(0,89,14);

drawTree(t, startLen);

}

void drawTree(Terrapin t, float dist) {

if (dist > 5) {

strokeWeight(4 * (dist/startLen));

t.forward((int)dist);

Terrapin copy = new Terrapin(t);

t.left(angle);

copy.right(angle);

drawTree(t, dist * decay);

drawTree(copy, dist * decay);

}

}This produces the following image (click for full size):

Let’s analyze this sketch.

At the top of the sketch, we define some global variables. These are variables that are visible throughout the sketch. The startLen variable defines the length of the first tree segment. The decay variable controls how rapidly the length of the tree segments decreases as more segments are added. The angle variable controls the angle of the “branches”.

The setup method is the same as the previous sketch: it just sets the window size, background color, and calls noLoop to specify that the draw method should only be executed once.

The draw method creates an initial Terrapin (turtle), positions it at the bottom of the window, and orients it so that it is pointing straight up. It also sets the drawing color to a shade of green. Finally, it calls the drawTree method with the initial Terrapin and initial segment length as parameters.

The drawTree method is where the interesting stuff happens. The if construct checks to see if the dist parameter is greater than 5: if not, then the method does nothing. If dist is greater than 5, then the method moves the Terrapin t forward by dist number of pixels. (Note that it is necessary to convert dist to an integer value.) Next it creates a copy of the Terrapin t, called copy. Both Terrapins (t and copy) are rotated by angle number of degrees, but in opposite directions. Finally, the drawTree method is called with Terrapins t and copy, and with the dist parameter set to dist * decay. (Since decay is a value less than 1, this causes dist * decay to be a smaller value than dist.)

Wait…what?

The drawTree method uses a technique called recursion. The idea is that to draw a tree, we use a single turtle to draw an initial segment, and then “split” into two separate turtles, each oriented at a different angle, and then use these two turtles to draw slightly smaller trees. In other words: a tree is a segment (you can think of this as the trunk, or a branch) that splits into two smaller trees. However, these smaller trees are formed in exactly the same way as the overall tree. Since the drawTree method draws a tree (whose size is based on the value of the dist parameter), it makes sense for the drawTree method to call itself to draw the smaller trees.

In programming, recursion only works if it “bottoms out” at some point. That is the purpose of the if construct: once the segment length (dist) falls below a specified minimum threshold, the process stops. You can think of this as occurring at the “leaves” of the tree. Without the if construct, the recursion would never “finish”.

Try experimenting with this sketch. What happens if you change the values of the startLen, decay, and/or angle variables? What happens if you use a minimum segment length threshold other than 5? Could you make the angle vary? Could you introduce some randomness?

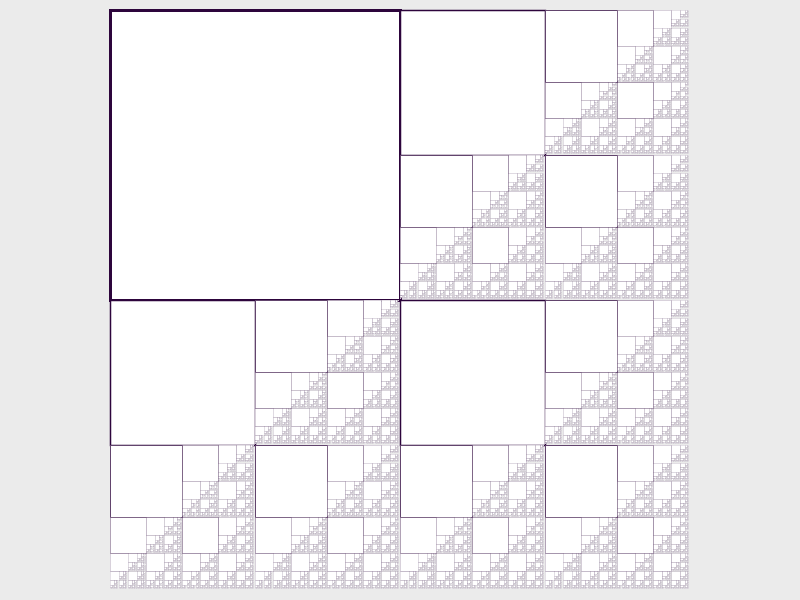

Example sketch 3: squares

Fractals can be created by simple rules. For example, let’s say we want to create a fractal image in a square area. Here are some possible rules

- Draw a square in the upper-left quadrant

- Recursively draw fractals in the lower-left, upper-right, and lower-right quadrants of the area

As with the fractal tree, we need to ensure that the procedure eventually “bottoms out”. So, if the width of the area in which a recursive fractal is drawn fall below a minimum threshold, we do nothing.

Here is the code:

void setup() {

size(800,600);

background(235);

noLoop();

}

void draw() {

stroke(45,5,60);

drawSquares(110,10,580,580);

}

// The parameters describe a square area with upper-left

// corner at x,y, width w, and height h

void drawSquares(float x, float y, float w, float h) {

if (w > 2) {

// Draw square in upper-left quadrant

strokeWeight(3 * (w/580));

rect(x, y, w/2, h/2);

// Recursive fractals in the lower-left, upper-right,

// and lower-right quadrants

drawSquares(x, y + h/2, w/2, h/2);

drawSquares(x + w/2, y, w/2, h/2);

drawSquares(x + w/2, y + h/2, w/2, h/2);

}

}Note that this code does not use turtles, but instead uses normal Processing drawing functions.

Here is the image produced (click for full size):

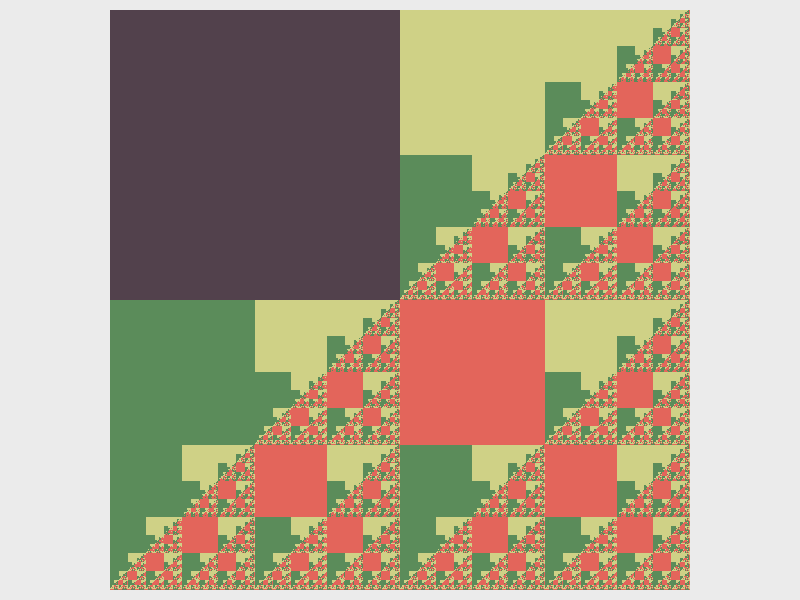

Try modifying this program. What happens if you comment out one of the recursive calls to drawSquares? What happens if you change the stroke color before each recursive call? What happens if you draw a different shape instead of a square? What happens if you fill the squares with a solid color? Could you create a similar fractal using a different shape, such as a triangle or rectangle?

I messed around a bit and came up with this variation (click for full size):

Your turn

Think about how you might use a fractal or other generative technique in the sketch you are working on as part of Assignment 3.